Trump, Gisèle and how to turn a narrative on its head

The story of 2024, as shaped by a perpetrator and a victim

Fake news, I’m afraid

I was listening to the In Our Time podcast about Plutarch’s Lives just before Christmas.

The Greek writer Plutarch (born 46 AD) considered two lives and united them through a common theme: character, virtue, vice and so on. And while Plutarch has often been called the father of biography, the In Our Time experts made the interesting point that this narrative technique, the parallel lives, has not been repeated in 2000 years of subsequent biography.

But at the same time I was listening to the broadcast, people were drawing parallels between two seemingly incompatible lives: those of Donald Trump and Gisèle Pelicot.

They were brought together by the annual debate about who should be named Time magazine’s Person of the Year. Should it be Trump, who had just won his second US presidential election? Or Pelicot, the French woman who was drugged, sexually assaulted by 83 men, and who waived her right to anonymity and sat in an Avignon courtroom for week after week of her husband’s trial as they showed the videos he made of the abuse?

Here’s where these two lives meet.

Trump has himself been convicted of being liable for sexual abuse; and has been accused of sexual misconduct by 26 women since the 1970s. He has boasted that his celebrity allows him to molest women in public.

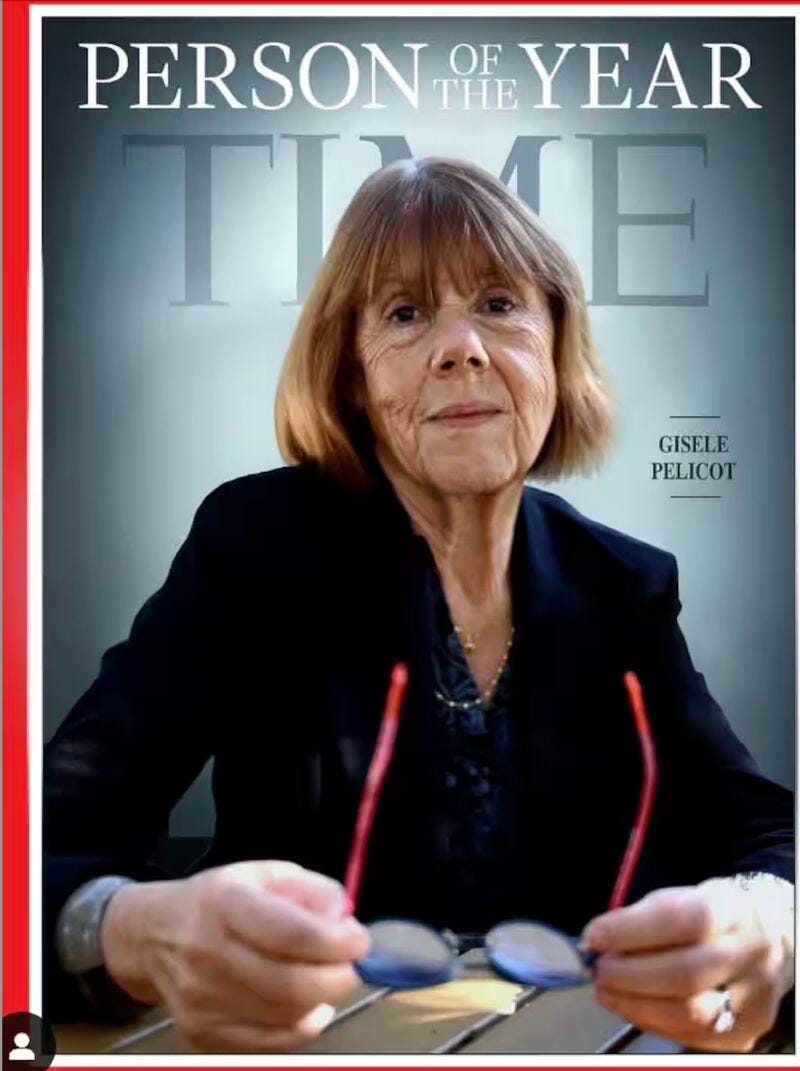

Time chose to honour the sexual aggressor, not the victim of sexual aggression. Outraged women – and maybe a few men, though they were, in truth, pretty inconspicuous – shared mock-ups of the cover as it should have been – with Pelicot as the Person of the Year.

I’ll come to the Time decision in a minute. But first, I have been thinking in a Plutarchian way about the myriad ways the lives of these two people, born just six years apart in 1946 (Trump) and 1952 (Pelicot) converge.

The theme is shame.

Inside an inverse universe

Forever, women have been made to feel ashamed of being exposed in public. Rape victims hide away, or decide not to act, out of shame.

Gisèle made the obvious point that it is her husband and his cabal of rapists who should feel shame, not she.

It may be an obvious point, but it’s one we seem to have missed throughout human history and within its multitudinous cultures. That’s why her decision (and the dignity with which she followed it through) seemed not only brave but genuinely radical and game-changing.

Yet Trump changed the shame-game, too, through his own audacious act of inversion.

Once, in normal cases involving normal public figures, any one of those 26 allegations, let alone a courtroom conviction, would have been enough to sink the perpetrator’s career for good. When Trump’s ‘pussy-grabbing’ boast became public in 2016 as he made his first run for president, experienced commentators said he was finished – shamed out of the race.

Why wasn’t he? Partly because what he said in that taped conversation was proved dead right. ‘When you're a star they let you do it. You can do anything,’ he said. He was talking about women, but could equally have been speaking about half the American electorate.

But the radical part was still to come. Trump was about to take shamelessness to a new level.

He turned the narrative on its head. The sexual misconduct case, like the ones for fraud, false accounting and the rest, were part of a ‘witch hunt’. The perpetrator became the victim: aggressive became passive. The more times he appeared, bowed head, in court, the more Americans came to see him as the target of a state-wide conspiracy by his political opponents. The big guy, the millionaire who made his name as a reality TV bully, became the little guy forced to remain silent while the blows rained down.

In this new looking-glass world, shame and victimhood shape-shift in bizarre and even comic ways. I was one of those British voters who found the experience of Liz Truss’s short-lived Premiership look-away embarrassing; for all my disdain and dismay at her folly, a part of me suffered for Truss, wondering how can one person live with that much ridicule and shame?

I needn’t have worried. There’s no shame. For Truss, too, it turns out, was a victim, brought down by the dark forces of global capital and power. She’s just fine, and there are plenty of ultra-conservative conference goers in the USA to tell her so.

Just fine, actually: Liz Truss, speaking at the influential far-right Heritage Foundation

Time magazine: only one life matters

A Caesar returns to his pantheon

So, let’s go back to the Time magazine conference room as they weighed up their 2024 choice.

I’ve some experience of these conferences and debates. Some of them are long, impassioned and bad tempered; others are pretty straightforward. This seems to have been one of the latter.

Sam Jacobs, Time’s editor-in-chief wrote ‘in many years, that choice is a difficult one. In 2024, it was not’.

The Person of the Year was Donald Trump. The write-up begins with a borderline slavering description the reborn imperial court at Mar-a-Largo:

Three days before Thanksgiving, the former and future President of the United States is sitting in the sun-filled dining room of his Florida home and private club. In the lavish reception area, more than a dozen people have been waiting for nearly two hours for Donald Trump to emerge. His picks for National Security Adviser, special envoy to the Middle East, Vice President, and chief of staff huddle nearby.

The writer notes that a selection of songs is. playing, including Abba’s The Winner Takes It All.

And that might be our reborn Plutarch’s obvious conclusion. The winner does take it all. When you're a star they let you do it. You can do anything.

Of course, there was not not even a debate in the Time office. This man defines an era. Who will remember Gisèle Pelicot’s name in a couple of years – next month, even?

And yet.

In Plutarch’s time, a cult founded in Palestine was beginning to cause a little consternation and interest around the Roman world. He doesn’t mention Christianity in his writings, although scholars are pretty certain he must have been aware of its growth and, possibly, the teachings of Jesus. And primary among those teachings is another mind-boggling inversion: that the meek will inherit the Earth. The right response for the small person oppressed by power, tyranny and vice is to turn the other cheek: bear witness stoically and courageously.

Astonishingly, that philosophy and its founder would outlast empires and become more powerful than any number of Caesars, dictators and presidents.

I don’t suppose that the Christian conservatives who laid hands on Mr Trump during his campaign will agree with this. Maybe they persist in seeing this Caesar, this man of might and violence and wealth, as a kind of Jesus.

History is unlikely to endorse that narrative. Maybe in time, if not in Time, Gisèle Pelicot will be seen as the person of 2024.

One observation, perhaps relevant to Gisele’s stand, is that the ‘turn the other cheek’ approach taught by Jesus is not one of timidity. The powerful would feel empowered to strike the vulnerable with the back of their hand, symbolising contempt. To turn the other cheek means to say - “if you are going to strike me, you must do so with your open hand and thereby lose your imagined superiority in relation to me”. This, it seems to me, is what Gisele has done.

Very interesting and the influence of nonentity celebrities is truly shocking. Shame on TIME I would say.