Writing, science and the law of levity

Why do writers and broadcasters think they have to present science in a 'lighthearted' way? The YouTubers and conspiracy theorists don’t

Not remotely scary: Rutherford and Fry. BBC

Anyone passing my house on a sunny afternoon last week would have heard raised voices. Two men were clearly having an extremely heated argument about something. But what?

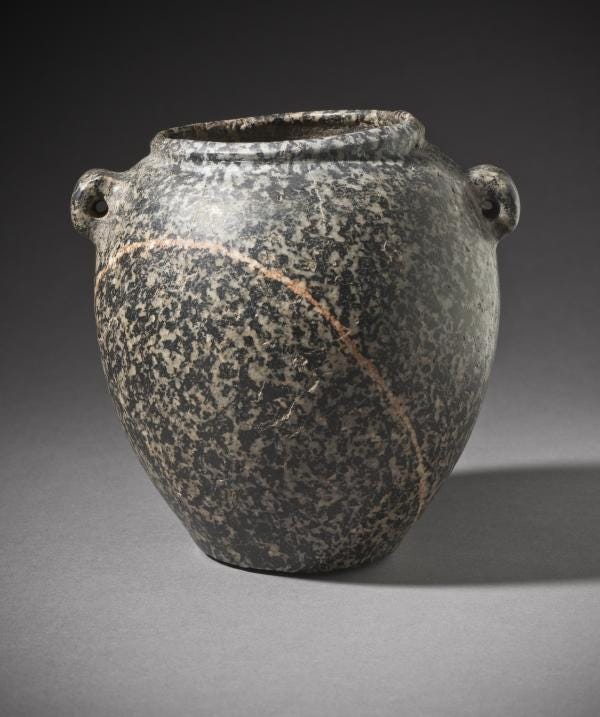

As the owner of one of those voices, I can clear up the mystery. I and my neighbour W. were having a violent disagreement about Egyptian vases.

I won’t go into great detail, unlike the YouTuber he follows who has done hours of videos ‘proving’ that Ancient Egyptians weren’t advanced enough to make artefacts of such incredible precision.

He didn’t say what ‘advanced’ means. Still, as these vases are incredible, that must mean that another, more sophisticated civilisation, or maybe aliens, did the work.

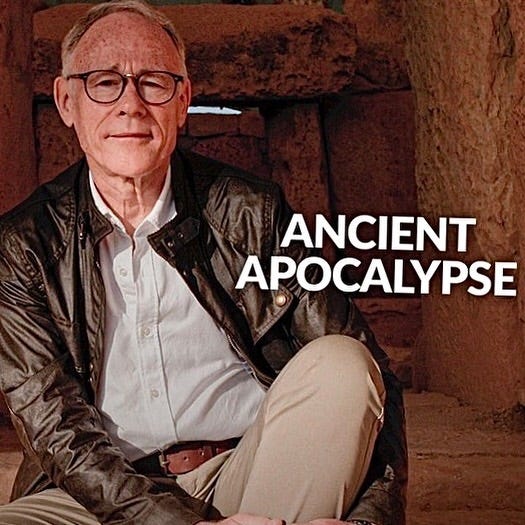

His research follows the theories of Graham Hancock, the sociology graduate and journalist whose books and Netflix documentaries argue that the archeology establishment has got it all wrong and ancient wonders were the work of a lost and advanced civilisation who unfortunately got wiped out 12,000 years ago.

I am great friends with my neighbour, who knows a lot about a lot of things. But when it comes to history, politics and the like, I am very suspicious of the people and places he gets his knowledge from. I am also uncomfortably aware that I am fighting a losing battle, as, like him, more and more people turn away from traditionally trusted and evidence-based sources of knowledge and towards theories that are a lot less boring.

Hence the shouting. I was shouting on behalf of the archaeologists (‘discredited’, said my neighbour) and scientists everywhere.

And it’s frustrating because those groups are getting their response to the YouTubers and keyboard Indiana Joneses so wrong. And that’s all down to something we in the writing and branding game call Tone of Voice.

The Law of Levity

The ‘lost civilisation’ theses has had the most airtime on Netflix, where Hancock’s Ancient Apocalypse has been viewed, according to one analyst, by between seven and nine million people, which is good news for Netflix’s management, whose numbers include Hancock’s son.

BBC Radio 4 has around nine million listeners a week – but that includes its flagship news and current affairs programmes and popular music stations. Figures for science programmes are not listed separately, but we can assume they do not make a hugely significant contribution to the overall figures.

Still, it was to one of those programmes, The Curious Cases of Rutherford and Fry that I went to see what they made of Ancient Apocalypse. I learned a lot from their programme, The Puzzle of the Pyramids and it gave me plenty of ammunition for my next shouting match with W.

But the programme also annoyed and depressed me.

Here’s why. At BBC Radio 4 and elsewhere in mainstream broadcasting there operates something I’ll call The Law of Levity.

It says:

If thou art making a programme about science, thou must make it lighthearted and jokey lest the listeners be terrified they won’t understand it or find it boring.

So you get solid scientists and excellent communicators like Dr Adam Rutherford and Professor Hannah Fry, make them dress up like Victorian detectives, pull silly faces, wear false moustaches and then you take a publicity shot. This is fun. Moreover, the humanities graduates who commission these programmes are happy because they have managed to put your science programme, which they don’t understand, into a format they do – Sherlock Holmes and the like.

Off they go in the pyramids programme, giggling at ‘YouTubers’ and making gags about conspiracy theories (‘It’s NEVER aliens, ho ho’).

Contrast this with the programmes Hancock and the vase expert, computer science graduate and self-taught archeologist Ben van Kerkwyk of UncharteredX.

Graham Hancock. The leather jacket denotes serious archeological expertise

They are never anything less than deadly serious. They are going to take you painstakingly through their research. They are not going to dress it up or make jokes. This matters. The only time they change their tone of voice is when they deal with the academic establishment that seeks to discredit that research. Then they get hurt and angry, as any victim of an establishment campaign is entitled to be. Of course the academic gatekeepers are going to rubbish my original and groundbreaking research. They are protecting themselves and their grants. It’s what these people do.

And of course the academics are going to be patronising and pretend these seismic discoveries are nothing more than pseudoscience or even science fiction.

Laugh at your peril

Getting your tone of voice wrong – or right – has big consequences. The conspiracy theorists are not joking: they never joke. Of course the medical establishment is not going to tell you the truth about vaccines. Of course climate change is a hoax devised to destroy the West’s economic superiority. Of course those so-called experts are going to patronise and laugh at you.

The truth hurts, but not as much as the lies. I’ll tell you what hurts when – usually against my better judgement – I get into rows with mates who espouse these once far-fetched and fringe opinions that have moved, in the Trump era, into mainstream belief and actual policy. I think of all those researchers measuring ice cores in Antarctica or digging for hours in a desert hole, patiently recording data for hours, decades, lifetimes to add to a weight of evidence which to them seems overwhelming but which gets reduced to a handful of dust because some guy with a webcam and an agenda gets invited on the Joe Rogan podcast.

Obviously faked shot of a researcher from the British Antarctic Survey

I think of children suffering painful and sometimes life-threatening conditions because of anti-vaxxers and the failure of public health people to counter them.

The character and skills that research requires are not the character and skills required to make your case to an easily-bored electorate scolling on their phones. The scientists need to take another approach. The Law of Levity is just going to carry on bringing them down.

Come on. Be serious

Scientists can start by cutting the jokes and trying to be all ‘accessible’. Take on the charlatans when it’s clear that’s what they are. As for the entrepreneurs who offer serious evidence for far-out theories, consider the evidence fairly and ask why it hasn’t been peer-reviewed or published in an academic journal (it never is). Be civil and firm and never make patronising jokes.

Will this stop the tide? No. I am detecting an air of defeatism among the bodies who are trying to support proper science. Here’s an example: the Meningitis Research Association in an article entitled How to respond to anti-vaccers:

If you have felt the devastating impact of a vaccine-preventable disease in your life, it can be very distressing to come across ‘anti-vax’ views. This is particularly true if you have been bereaved, and you know that your loved one would still be here if they’d had access to a particular vaccine. In this situation, when we encounter ‘anti-vax’ sentiment, our initial impulse is to respond with anger.

You bet it is. My impulse would be to get extremely angry, even though I have not had my life devastated by the preventable death of someone close to me.

Anger also makes for great copy. But the Association counsels against it:

Evidence suggests that angry comments on social media can polarise people’s views further and they may be even less likely to accept any scientific or medical advances.

Instead:

…experts suggest that the aim should be to acknowledge and empathise with their concerns before working to alleviate them – rather than immediately dismissing concerns, or trying to replace them with alternative information.

Well, I guess they’d know. Use language to appease and assuage, not argue and persuade. It sounds like the language of defeat to me, rather like those world leaders who bite their tongues while the President of the United States sitting next to them has tantrums and says palpable untruths about their country, or the medical chief, appalled but silent, who stands and watches while that same president suggests we inject ourselves with disinfectant .

"I'm not a doctor,” said Mr Trump on that occasion. “But I'm, like, a person that has a good you-know-what."

The Law of Levity demands that we humour him. He can’t be serious, after all..

Are there any lessons to be learned I wonder from how interventions with cults are handled. (However 'cult' may now be a loaded word. Is the polite term 'those with significantly divergent but still totally valid opinions from the mainstream view'?) :(

[Emoji used intentionally - see earlier Forthwrite discussion on legitimacy or not of emojis in comms]