Botox copy

No, I am not promoting beauty treatments. I'm looking at what happens when words become frozen and expressionless

An editor at work. Photo by Studio Michael França on Unsplash

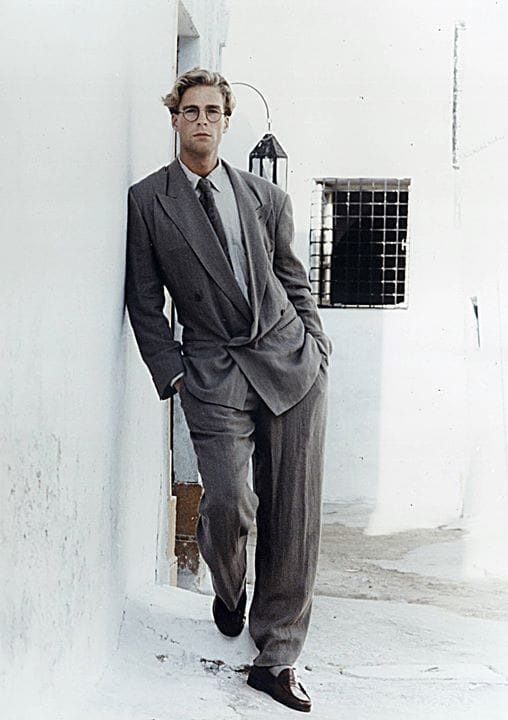

I am not an expert on the subject, so I can’t tell you how big an influence Giorgio Armani had on women’s fashion. But I know a little bit about men’s clothes. If, like me, you were a man working in the creative and media industries in the last two decades of the 20th century, Armani mattered a lot.

The Italian designer’s suits progressed from desirable to compulsory, from a fashion choice to a kind of uniform. The classic box-cut English suit was for City boys and politicians. Americans draped themselves in descendants of the Zoot. With Armani, you got structure and fluidity, smartness and casualness before the term smart-casual got into wide circulation.

Style is a word that applies to the way we dress and the way we write. If Armani were a passage of writing, it’d be, first, correct and elegant. It would avoid flashy adjectives and current vogue words. But it would be contemporary English too – no pompous constructions or affected archaisms: easy to read and easy to write.

Armani died on 4 September. I was interested to see how his life was captured in writing. And how it was captured told me a lot about the state of modern corporate English and the way powerful people and the people who advise them choose their words.

Awkward/brilliant timing (depends on your perspective)

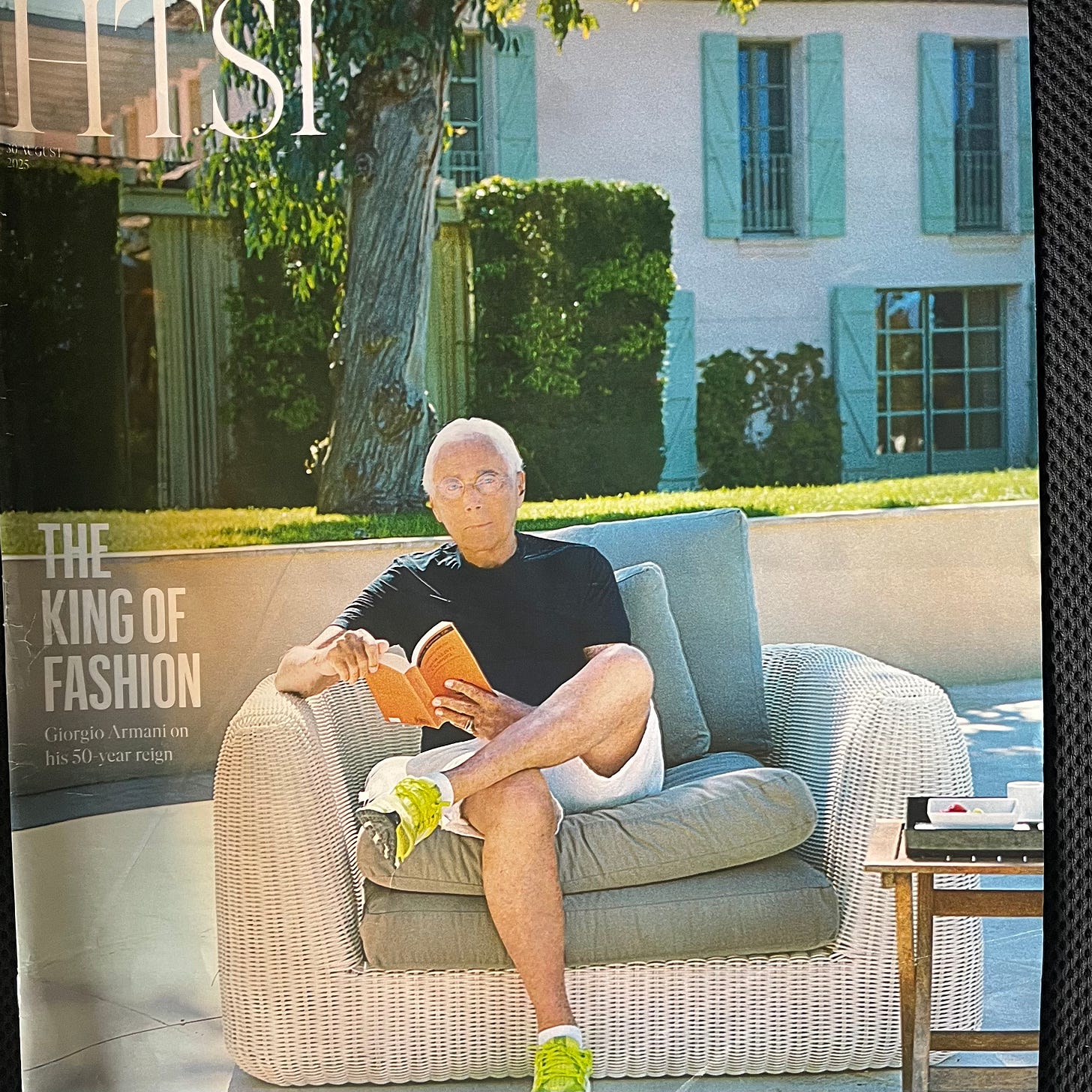

Editors usually look for a peg, a news story or trend to hang a story on. But when the Financial Times’ How to Spend It magazine – or, as we should call it in these rushed times, the FT’s HTSI – landed a rare interview with Armani, it didn’t need a pretext. Interviews with the name on one of the world’s most prestigious labels don’t come along often.

As it turned out, it had the hook of the century: Armani died five days after publication. The six-page tribute to a man ‘retaining an iron grip’ on his empire became an obituary avant le fait.

The HTSI cover shot showed Armani reading a book on a cane sofa outside a French-style chateau. In navy blue t-shirt, white shorts and green trainers, he looked every inch the tanned, fiftysomething entrepreneur having a break between workouts: tanned skin, muscular legs, barely a line on his face.

The fact that Armani was 91, and no one looks like this at 91, is just one of the photographic fictions we all comply with. Somewhere around the start of the 2000s, celebrity photographs ceased to be photographs and became illustrations of an idealised human being’s face and body if it’s miraculously not been subject to the laws of gravity for 10, 20, or 50 years.

It was an extremely rare and wilful star who takes issue with being preserved in the digital version of aspic. One was the actress Kate Winslet, who said of a GQ shoot in 2003 that the art director has slimmed down her legs ‘by about a third’, saying: ‘I do not look like that and more importantly I don’t desire to look like that.’

(Mind, Winslet’s Vogue cover shoot of 2013 prompted writer Emma Broackes to say ‘her hair is detachable plastic; her eyes are like marbles. Her expression, which I guess is her own, albeit under [photographer Mario] Testino’s direction, is sort of mysterious with a touch of, “Help! I’ve been laminated!’’. I guess people move on….)

Anyway, photographic distortion is a tired and pointless debate in an era when we all have a portable Mario Testino in our pockets. What interests me is the major surgery job that’s gone on inside – in the copy.

You can quote me on that (with conditions…)

As part of the writing courses I run with Kerry Smith, we have a module called How to make your boss sound human.

It’s popular, especially with communication professionals. They’re writing a media release or a piece of website content and they need a few words from the higher-ups. The boss says, write it and I’ll sign it off. The comms team knows that this is a recipe for bland, robotic sentiments anyone (or your nearest AI site) could voice. After all, you’re not going to risk putting colourful, provocative, idiosyncratic words into your boss’s mouth, are you? – even if the said boss is colourful, provocative and idiosyncratic (it happens).

So, you try to get some facetime with the boss. I once point-blank refused to ghostwrite a CEO’s article because I’d never met the man and didn’t know how he sounded. His minders relented. The said CEO, majorly INTJ, hated every second, but it made for a decent and, importantly, human piece.

The FT people put out calls for tributes from fashion and Hollywood A-listers to the man they universally (and, I suspect, contractually) called Mr Armani.

A test. Work out which of these quotes is from a real person and which was made up for them, possibly by a committee:

Mr Giorgio Armani is synonymous with classic elegance. His vision has long shaped the timeless gold standard.

He is a cultural icon. His creative vision has redefined elegance.

I once asked him, how does it feel to arrive at this place…? He said something like, ‘Just at the point when you understand what it’s all about you run out of time.’

His shapes, fabrics, colours and construction were all brand new.

By introducing the fluid suit in the 1980s, he promoted ideas of casual elegance – mixing formality with a relaxed sensuality – often through using lighter fabrics and removing the lining. It was such a rebuff to the power dressing of the time.

Mr Armani has straddled fashion like a colossus. Mr Armani’s timeless style ensures his creations will endure forever.

The answer, of course, is we don’t know. But I am prepared to bet a lot of Italian lire that (1), (2) and (6) are not words that came directly from the lips of, respectively, Renee Zellweger, Remo Ruffini and Daniel Craig. Whereas Oswald Boateng (3), Paul Smith (4) and Andre Bolton (5) are real sentiments from people who had evidently thought about the question.

Daniel Craig – or is it?

Those three answers, from two designers and a curator, are from people who understand a designer’s life and craft. You learn something from those quotes. You don’t learn anything from cliches like ‘colossus’, ‘timeless’ and ‘icon’.

Those (I believe) manufactured quotes are the writing equivalent of airbrushing.

Or maybe a better analogy is botox. Botox copy is what happens when you inject an English sentence with a neurotoxin that paralyses it. You get words that might look superficially attractive, but there is no personality or warmth in them – it’s all been smoothed out. Botox fillers are notorious for inhibiting expressiveness – a smile, a frown, a nuance. Botox copy does the same. You rob language of its expressiveness.

A quick note on legends

Language evolves – two words those of us who keep a wary eye on words that get misused and weakened should repeat as a mantra every day.

Armani was widely described as the ‘legendary’ designer (icon etc). But he isn’t the only legend to have passed away recently. The first page of my Google search reports the passing of TV legend Nigel Latta, Hollywood legend Renato Casaro, another Hollywood legend Robert Redford, football legend Ken Houghton and ‘absolute’ legend Tony ‘the Tiger’ Knight, who was ‘well-known across Stoke-on-Trent for taking part in the Potteries Marathon’.

The pedant in me winces every time the word comes up. I wish we could go back to the time when the epithet ‘legend’ was reserved for characters who may or may not have existed (King Arthur, Robin Hood) and the stories associated with them. But – language evolves. Your next door neighbour can be a legend because he lent you a step ladder.

Nigel, Renato, Ken and Tony may have achieved much in their chosen fields. Still, in my book there is only one true legend – in the modern sense – on the above list and that’s Robert Redford. Maybe we need a new word that’s a step up from the legendary status for people like the actor and director. Mythical?

Robert and Tony: RIP.